A warning to readers: This story is an unvarnished, unsanitized firsthand account of the Second Battle of Fallujah that features descriptions and images which are candidly disturbing. In telling this story, I promised my fellow Marines that I’d not sugarcoat our expertise. This story is revealed in collaboration with The Struggle Horse. To listen to us in our personal phrases, you’ll be able to hearken to The Fallujah Information, an eight-part audio sequence together with conversations and interviews with Marines I served with from Alpha Firm, 1st Battalion.

Slim metallic cages sit empty in a darkish, damp nook of the execution room. Bloody handprints mark the windowless mud partitions. Human feces are piled within the nook. The air smells of urine and loss of life.

Close by stands a makeshift altar. Dried blood stains the filth beside an empty digicam tripod. The ground feels cheesy with each step. A Quran rests on a lectern. Knives and medical provides are strewn concerning the floor. The black flag of Al Qaeda hangs on the wall.

A few of us step outdoors. Others argue over whether or not the bloody handprints belong to the sufferer or the executioner. Some guess what number of heads had rolled throughout the ground, or whether or not the executioner used the straight-edge or the serrated knife. Did they like effectivity or ache? The darkish humor dulls our actuality and makes the scene extra palatable. It’s 2004, roughly 10 days earlier than our households again house will rejoice Thanksgiving. As our squad of Marines resumes our patrol by way of Fallujah, Iraq, a few of us pledge to kill ourselves—and one another—earlier than we’ll ever be caged by the jihadis. Each dialog circles again to the cages and the killing. A number of Marines wrestle to eat dinner. Nation Captain Hen appears to be like even much less appetizing. The considered being trapped in a cage retains me awake.

For the following month, fight strips away our humanity as we patrol avenue by avenue. Fight brings out the best possible and worst in us. Most chuckle concerning the loss of life. Those who break down are despatched again to the bottom. Others {photograph} corpses and detainees. A number of volunteer to kill the canine feasting on human stays. With each firefight, we drift farther from the values we as soon as held pricey and the lads we as soon as had been. Fathers and sons. Blue-collar employees and faculty graduates. And even the pompous son of a billionaire.

All modified eternally by conflict.

After 5 weeks in Fallujah, it looks like many people have misplaced our manner and aren’t fazed by the depravity surrounding us. A few of us chuckle at a kitten crawling out of the chest cavity of a corpse, and after one in all my rockets transforms a human being right into a bloody shadow on a wall.

Most of us rejoice the crumpled our bodies, mangled by the rockets and bombs. Some {photograph} the corpses bursting like fight pinatas after bloating underneath the desert solar. We cheer as a bulldozer buries enemy fighters alive.

The dozer is bulletproof. We aren’t. And we’ve all rationalized that they’re going to die anyway.

Then, one night time shortly after Thanksgiving, we’re woke up by the sound of a Marine from one other battalion beating a cat to loss of life towards a wall. He releases its lifeless physique from the empty inexperienced sack, and it falls from our second-story window onto the road under. The animal was making an excessive amount of noise, he says. He then lays down beside us.

All of us return to sleep.

It’s been 20 years now—half our lifetimes—since we fought within the bloodiest battle of the worldwide conflict on terrorism. President George W. Bush had simply received reelection, regardless of considerations over the Iraq Struggle and the lies that led us there. It had been 18 months since he had declared “an finish of main fight operations” in Iraq.

However the insurgency was rising stronger. Militants boobytrapped roadways with explosives and beheaded Iraqi collaborators in kill rooms—just like the one we found—executions that had been filmed to ship a message each to the Iraqi residents and overseas invaders. However nothing symbolized the disdain for our presence in Iraq greater than the March 2004 execution of 4 US contractors from Blackwater who had been crushed, lit aflame, dragged behind automobiles, and hung from a bridge in Fallujah. On the time, I used to be an 18-year-old Marine contemporary out of boot camp who didn’t know any of that story. However seven months later, right here I used to be, in November 2004, as one in all practically 13,000 American, British, and Iraqi forces ordered to combat Operation Phantom Fury, a 46-day battle in the course of the US occupation of Iraq and the heaviest city fight Individuals had seen for the reason that 1968 Battle of Huế Metropolis in the course of the Vietnam Struggle. The battle demonstrated that what we thought a yr in the past had been pockets of resistance was, in truth, a full-blown insurgency.

Greater than 4,000 enemy fighters armed with rockets, machine weapons, and explosive units fought from trenches, tunnels, and booby-trapped houses.

By the top of the battle, about 110 members of coalition forces had been killed and greater than 600 had been wounded. Roughly 2,000 enemy fighters died, and 1,500 had been captured. An estimated 700 civilians had been killed, and by the top of the battle, practically half of town lay in ruins. It marked a brand new section in a conflict that was rapidly spiraling uncontrolled and would in the end price US taxpayers greater than $728 billion and result in the deaths of greater than 4,500 coalition troops and greater than 32,000 others wounded. In complete, no less than 200,000 Iraqi civilians had been killed.

For 20 years, the women and men ordered to combat in Fallujah—and different battles of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—have lived with these traumas, and regardless of our collective successes as we continued serving or returned to civilian life, many people nonetheless ended up in a field.

The ethical harm. The medicine. Alcohol. Suicide. Divorce. Cancers from the poisons we had been uncovered to. The record goes on and on.

For the final twenty years, I’ve averted studying the books that had been written about our battle. I haven’t watched the documentaries or revisited the information tales. I distanced myself from the reunions and the younger males who had been as soon as my shut associates.

As I write this, I’ve tears in my eyes. I’m afraid of what this journey will do to me and what the response will probably be. However the additional I journey in life past the house-to-house combating, the extra I ponder how my physique—and my thoughts—survived it, and whether or not I nonetheless will.

Everybody again house anticipated us to be killers and diplomats on the identical time. We succeeded on the previous and failed tragically on the latter. If I had been a resident of Fallujah who returned house to the destruction after our battle, I’d commit my life to killing Individuals.

We didn’t simply destroy the enemy, we thrived at it. And many people grew to take pleasure in it. But we obliterated components of ourselves alongside the way in which.

We defecated in individuals’s bathtubs to keep away from being shot on the street. My rockets broke prayer beads and incinerated Qurans. Grenades blew aside heirlooms. We destroyed wedding ceremony images as we knocked over dressers and flipped mattresses throughout our searches. Throughout town, Marines set houses ablaze. We littered neighborhoods with white phosphorus, unexploded ordnance, and burn pit ash. We blew up childhood bedrooms, faculties, and mosques.

The destruction was a tactical necessity. However it was additionally enjoyable.

Twenty years on, I now carry a heavier pack: the guilt that I may have completed much less. And extra. For 20 years, I’ve wished I had fired a rocket into an enemy stronghold as an alternative of letting Lance Cpl. Bradley Faircloth kick in that door. And for 20 years, I haven’t stopped fascinated by the time we had been ordered to face down and never shoot a gaggle of enemy fighters utilizing girls and youngsters as human shields. The jihadis scurried down an alleyway.

Our collective want record of do-overs is neverending. However the record of selfless and heroic acts we witnessed in Fallujah can also be infinite.

Earlier than Fallujah, I assumed I understood conflict. Bullets and blood. Our bodies and bandages.

Some stay. Some die. Oohrah.

However what fight teaches you is that your circle shrinks to the handful of people who find themselves there with you. No person and nothing else issues. Not the flag. Not our households or fellow Individuals again house. Not a fictional hunt for weapons of mass destruction. Not the Iraqi individuals. And certainly not the politicians who despatched us to conflict. We had been ordered to combat and did no matter we needed to do to outlive. That is our story.

Marines are wounded. I rush to choose up the handset of the radio and start calling in a casualty evacuation. Location. Callsign. Variety of sufferers.

I can’t keep in mind what to do or say subsequent. I’m caving underneath the stress.

“You’re a bit of shit, and also you’re going to get everybody killed,” screams my squad chief, Sgt. Billy Leo, a 27-year-old from the Bronx.

“You’re a bit of shit, and also you’re going to get everybody killed.”

I’m 6,000 miles from the battlefield, and I’m making an important first impression.

It’s 2004 and I’ve simply graduated from the Faculty of Infantry, and that is my first coaching train as one in all third Platoon’s latest “boots,” probably the most junior Marines within the Corps. I’m an infantry assaultman specializing in demolitions and rockets, and I’m assigned to Alpha Firm, one in all 4 infantry items inside 1st Battalion, eighth Marine Regiment, at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

In fewer than 90 days, we will probably be patrolling the streets of Iraq collectively for seven months. I rapidly study—and Sgt. Leo reinforces—that I’m not prepared for fight and that I haven’t earned his belief.

The remainder of my week is a blur of standing guard, filling sandbags, workouts within the treeline, and no matter different “fuck fuck video games” could possibly be performed to show me—and my fellow “hopeless” boots—a significant lesson: Lives rely on proficiency, consideration to element, and an prompt willingness to observe orders.

After we wrap up our two weeks within the discipline, we’re shipped off to an deserted Air Pressure housing advanced close to San Diego often called Camp Matilda—a wasteland of asbestos and lead-based paints, damaged glass, and rusted metallic.

For weeks, we follow establishing automobile checkpoints, looking out detainees, and rehearsing infantry ways we’ll quickly use in Iraq. At night time, I lay on the ground of an deserted house and stare at uncovered insulation within the ceiling as I go to sleep.

After two months with my Marines, I journey again to the Boston space for 30 days of pre-deployment depart again at my childhood house, the place my associates from highschool inform me I’m loopy if I’m going to Iraq. They’re supportive of my service, however my enlistment has all the time confused them, they usually can’t fathom trusting strangers with their lives. I inform them that Sgt. Leo is among the massive the explanation why I do.

He’s a towering drive with a contempt for boastful leaders and is fiercely loyal to us. I barely know him, however I belief him. He’s bar-battered and continuously goes toe-to-toe with higher-ups to defend us from their flawed methods and pointless video games.

Solely he fucks with us.

Deep down, we all know Sgt. Leo simply desires to deliver us all house.

Again in North Carolina, we lay our uniforms on the bottom within the quad on the heart of our barracks. Marines with canisters of chemical substances stroll backwards and forwards and mist our clothes.

The chemical substances are to guard us from malaria and final all the deployment, they are saying.

Wash your uniforms twice, and they’re protected to put on, they are saying.

The following day, and practically each day till we deploy, we begin our mornings on that very same grass. Pushups. Situps. Grappling matches. Then we placed on our chemical-laced uniforms and lay out our gear again and again.

We clear our rifles and rooms. Then we clear our rifles some extra.

After work within the barracks, we drink. Lots. It’s massive boy guidelines. Underage? Doesn’t matter. Wish to throw a fridge off the third story? It higher be your fridge. Wish to see who can smash extra beer bottles on their head? Doc higher not must sew you up.

Marines funnel exhausting liquor from the third story. Some rent intercourse employees or hunt down comfortable endings at therapeutic massage parlors. Others inform tales of previous sexual conquests. Arrington brags concerning the dimension of his dick, keen to point out anybody who doesn’t consider the lore. Drunkards wrestle and combat. Our “give a fuck” is damaged, and all the boots will clear up the mess earlier than our morning formation. We’re going to conflict.

By the top of our first month in Iraq, the monotony of the beggars, the tan panorama, and our mission to “win hearts and minds” are killing our motivation and making us complacent.

Diplomacy is the Military’s job, not the Marines’.

For our first three months in Iraq, we aimlessly patrol Rawah, Hadithah, Anah, and different small villages. At Iraqi police stations, we barter copies of Playboy and Hustler for contemporary meals of rooster and rice. In every metropolis, we’re itching for a gunfight, however all we do is kill time. The one factor we’re combating is boredom.

None of us has misplaced our fight virginity.

In late October, we’re instructed we’re getting a change of surroundings and to pack solely the gear we will carry. We’re being relocated to Camp Fallujah. We do as we’re instructed. We’re unaware of the extraordinary combating elsewhere within the nation and that Fallujah is an rebel hotbed the place jihadis movie executions.

A number of days later, we strap our packs to the perimeters of 7-ton vans and trip into the darkness. What looks like an infinite string of army automobiles stretches to the horizon in both route. I chain-smoke Marlboros as I stare on the stars and go to sleep to the hum of knobby tires towards the asphalt.

After we get to Camp Fallujah, everyone knows one thing massive is about to occur. Hundreds of Marines from throughout a number of battalions are crammed onto the bottom. We repetitiously evaluate maps, follow casualty evacuation drills and clearing rooms, and go to a makeshift rifle vary to confirm the sight settings on our weapons.

Our leaders know a troublesome combat is forward of us, and their plan is shrouded by the fog of conflict and the uncertainty of violence.

A number of days earlier than the battle begins, our battalion is standing in a semicircle when an enemy mortar spherical slams into the bottom beside our formation and doesn’t explode. I take into consideration how fortunate we had been that the spherical was a dud. Dozens of us are standing within the kill radius. We erupt with a mixture of cheers, laughter, and screams.

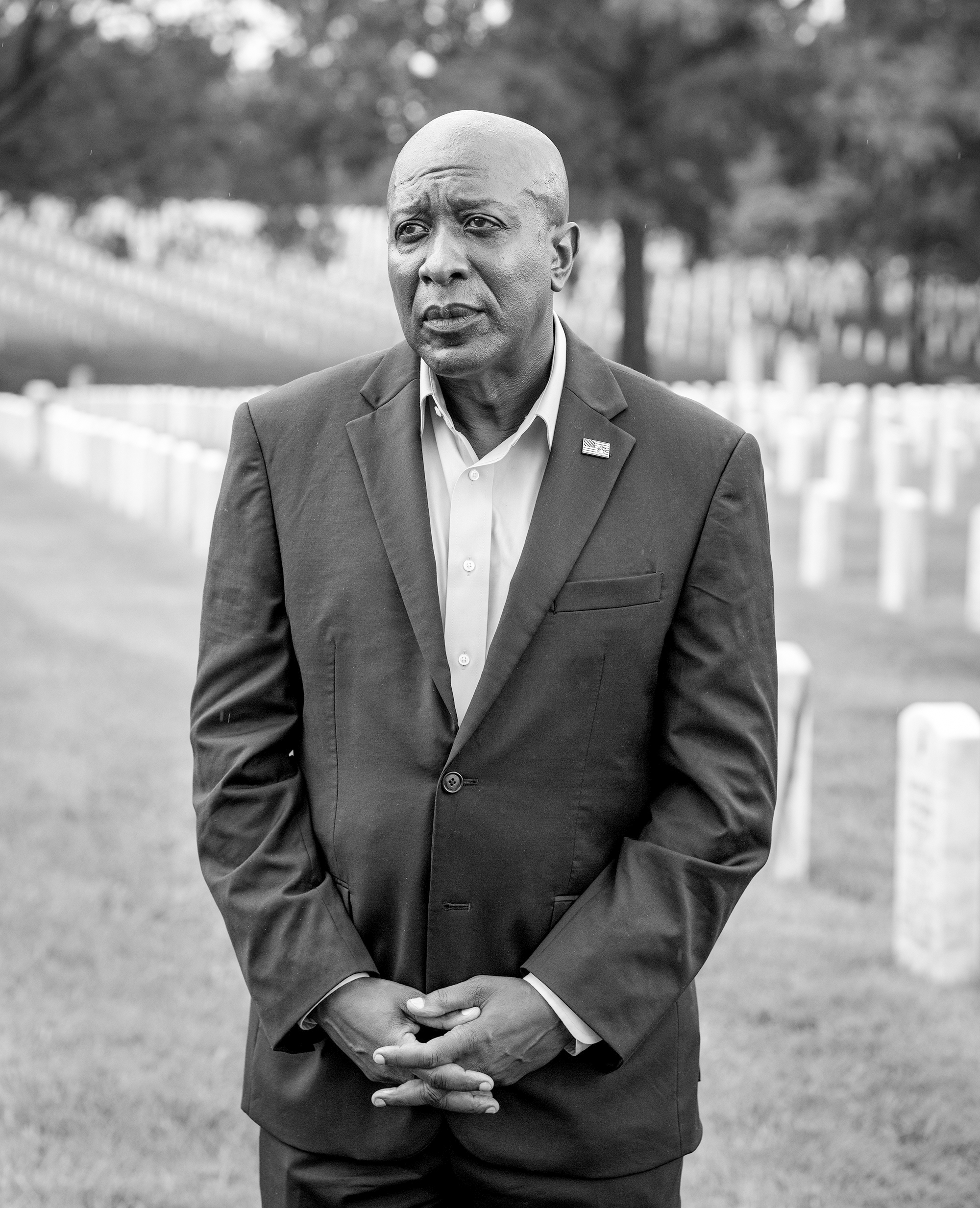

Our battalion goes silent as Sgt. Main Carlton Kent, a 47-year-old from Tennessee and the senior enlisted Marine for the upcoming battle, steps in entrance of us and appears out throughout a sea of desert camouflage. A few of us sit. Others kneel. Some stand.

“I’m gonna inform you one factor. It’s an honor for me to have the ability to serve with every one in all you exhausting chargers,” he says. “I imply, I look out right here, and it’s no distinction than after we took the rattling conflict over in Korea, we took it throughout World Struggle II, we raised the flag at Iwo Jima—it’s no distinction.”

“It’s no distinction than after we took the rattling conflict over in Korea, we took it throughout World Struggle II, we raised the flag at Iwo Jima—it’s no distinction.”

“Y’all are within the course of of creating historical past, and I’m very happy with you, and I’ve little question you might be gonna go in there and do what you all the time have completed—kick some butt.”

We stroll again to our constructing and await a briefing from our platoon commander, 2nd Lt. Douglas Bahrns, a 23-year-old who studied English at Virginia Navy Institute. As Bahrns walks into the room, Sgt. Leo tells us to sit down down and shut up.

Bahrns stands in entrance of us. Grains of sand float by way of immobile air as beams of sunshine creep by way of sandbagged home windows. Younger males sit mesmerized by the phrases echoing off partitions scarred by years of conflict.

By the desert confetti, Lt. Bahrns shifts between confidence and trepidation as he explains the main points of our mission to clear Fallujah of enemy fighters and what ought to occur when—not if—we’re wounded.

He tells us that inside town, we’ll face roadblocks, sniper positions, boobytraps, and greater than 300 well-constructed combating positions that make up a three-ring defensive posture. He explains that civilians have fled town, and our psychological operations groups have manipulated insurgents into making ready for an assault from the south. As an alternative, blocking forces will first encompass the southern facet of town, after which our platoon will probably be on the heart of a six-battalion, house-to-house battle.

Lt. Bahrns pauses usually, gazing into the darkness above our heads.

The fact of our mission is turning into clear. We all know that Bahrns, like Leo, desires to deliver us all house. Everyone knows that received’t occur.

The screams of 1000’s of US Marines roar into the gap as tracer rounds dance throughout the night time sky, by way of a barrage of air-burst white phosphorus and thousand-pound bombs.

For hours, we watch as munitions explode. A few of us ooh and ahh. Others tempo anxiously. Because the night time passes, we go to sleep to the sounds of warthogs and gunships. I cuddle with Phil Barker and Doc Frasier to remain heat.

Operation Phantom Fury is starting.

Process Pressure Wolfpack is the primary unit to breach town’s perimeter, and as they start taking sporadic hearth, a voice in Arabic echoes from the loudspeakers of a close-by mosque.

“Residents of Fallujah, get up. The infidels are right here. Kill them, kill all of them.”

“Residents of Fallujah, get up. The infidels are right here. Kill them, kill all of them.”

For 2 days, as the primary Marines push into town, I examine and recheck my gear, cinching my rockets tighter and tighter towards the 20-pound satchels of C-4 inside my pack, and wait to storm Fallujah. I ponder if the fight will probably be over earlier than we attain the outskirts of town.

I draw smiley faces on my grenades and write, “One free ticket to Allah” on an explosive. I snap {a photograph} that captures my misguided hatred. We play seize ass and Spades, and I make dozens of donut and det-linear expenses that can quickly make doorways disappear.

However principally, with every explosion or machine gun burst we hear, we marvel what will probably be like inside town. Who would be the first to die?

Shortly after 3 a.m. on November 10—the Marine Corps’ birthday—we strap on our gear and cargo into the tracked automobiles that will probably be both our chariots into battle or a metallic mass grave.

The diesel engines roar to life because the metallic ramp closes behind us. The earth crunches beneath us as we start our drive towards town.

We’re jostled backwards and forwards as we crash by way of rubble and particles. There are explosions and gunfire within the distance. Black exhaust seeps into the troop compartment.

Because the seconds go, our 20-minute drive looks like hours. I envision scenes from the Normandy touchdown throughout World Struggle II, the place machine weapons ripped by way of the lads crammed contained in the Higgins boats because the ramps lowered.

I shut my eyes and anticipate a rocket to tear by way of the facet of our automobile, remodeling us right into a stew of melted fats and charred flesh.

I really feel trapped and helpless. I would like out.

“One minute,” shouts the automobile commander. A few of us go silent. Others hype themselves up. “Let’s kill some hajjis,” somebody yells. We reply with a sequence of guttural screams.

Yut. Err. Kill.

However because the ramp lowers, the sluggish creak of the metallic door is all we hear. There’s near-complete silence as we run to our assigned sectors of Fallujah’s authorities advanced.

No gunfire. No explosions. No loss of life.

For the following few hours, I sit in a dilapidated workplace chair, recessed within the shadows of a second-story room of the federal government advanced. Because the solar continues to rise, the buildings to our south erupt with gunfire. I discover a person with an AK-47 poke his head round a nook.

I shoulder my rifle as he creeps round a mud wall and slowly begins to shut the 200 meters between us. The clear tip of my entrance sight traces the middle of his chest. Worry builds inside me. It’s the first time my coaching will probably be examined.

I pull the set off of my M16. The weapon’s recoil nudges my shoulder, and he crumbles to the bottom. The aroma of gunpowder fills the room. I hearth two extra rounds into his immobile physique and stare in amazement as he lies lifeless. I peer by way of one other Marine’s rifle scope to get a better look.

It can take years for my smile to fade.

I watch the solar proceed to rise throughout town’s skyline as loudspeakers blare the Marines’ Hymn by way of the streets.

Completely satisfied Marine Corps’ birthday, I feel.

Moments later, machine gunfire and rockets start peppering our place, and I’m ordered to the rooftop with my rocket launcher. I dash throughout the roof and hunker behind a small mud wall to defend myself from the bullets whizzing by.

As I carry my head, I take within the full Fallujah skyline for the primary time. Buildings stretch from horizon to horizon—a sea of tan dotted with minarets and smoldering fires. I watch as Capt. Aaron Cunningham, the maestro of our frontline symphony, stands calmly as bullets skip throughout the rooftop round him.

We’re surrounded by the enemy.

Then the second we’ve feared most lastly arrives. The primary Marine is killed.

Lt. Daniel Thomas Malcom Jr. is lifeless—shot within the again whereas calling in artillery. Jordan Holtschulte, a Navy corpsman from a close-by platoon, tried his finest to avoid wasting him.

Information about Malcom’s loss of life spreads throughout our unit inside minutes and stops me in my tracks. Earlier than Fallujah, I’d spent 4 months in convoys as his driver. Throughout our time collectively, I grew to respect his humility and mind. We spoke about his sister and his favourite books—I’m ashamed to say I’ve since forgotten these names. I by no means acquired to inform him how a lot I admired him or ask him concerning the burden he carried main our band of enlisted misfits.

I take into consideration how he liked to play chess, which to him was one more manner he may prepare his thoughts to defeat an opponent. If life had been a brilliancy—a deeply strategic chess mixture—he made his with brevity, successful a chess sport in 25 strikes, his age when he was killed.

His corpse is carried to a close-by automobile and pushed away.

Javelin missiles shriek by way of the sky. Machine gunners hearth from the rooftops. Artillery thumps within the distance moments earlier than a thunderstorm of metal rain pours round us.

Our squad is crammed right into a room on the south facet of the federal government advanced, ready to dash throughout Route Fran, the multilane freeway that separates us from our 3-mile, house-to-house battle by way of town.

Trying again, Route Fran was a ultimate buffer from the true carnage and a life-altering demarcation level for all of us.

As soon as we crossed over, life can be completely different.

The change can be eternally.

“One minute,” somebody yells.

My coronary heart is racing.

I’m scared.

The time passes immediately.

Yut. Err. Kill.

Sgt. Leo takes off throughout the street, and we dash behind him.

I jump over the middle median and rush towards the sidewalk. Electrical wires dangle from avenue poles. Rubble is scattered about. A thick black smoke dances within the air.

We peer by way of shattered home windows and damaged doorways as we go by outlets and workplaces broken by the airstrikes and rockets.

As we rush down the primary alley, second-story home windows erupt with gunfire. We’re pinned down.

Some Marines break off to clear close by homes. Cpl. Robert Day, a 24-year-old from Cellular, Alabama, sprints to the roof together with his machine gun and a crew of snipers in tow. Bullets whiz and ricochet round him, peppering him with chunks of brick and mortar. Day presses his shoulder into his machine gun as a fighter with a backpack filled with rockets sprints down a avenue.

Search. Traverse. Hearth. Repeat.

Concurrently, the remainder of our platoon maneuvers down the road, returning hearth and bounding from place to place.

“Get these rockets up right here!” Sgt. Leo screams, from the entrance of our patrol. He’s standing beside a compound wall and is unfazed by the firestorm surrounding us.

He’s calm amid the chaos.

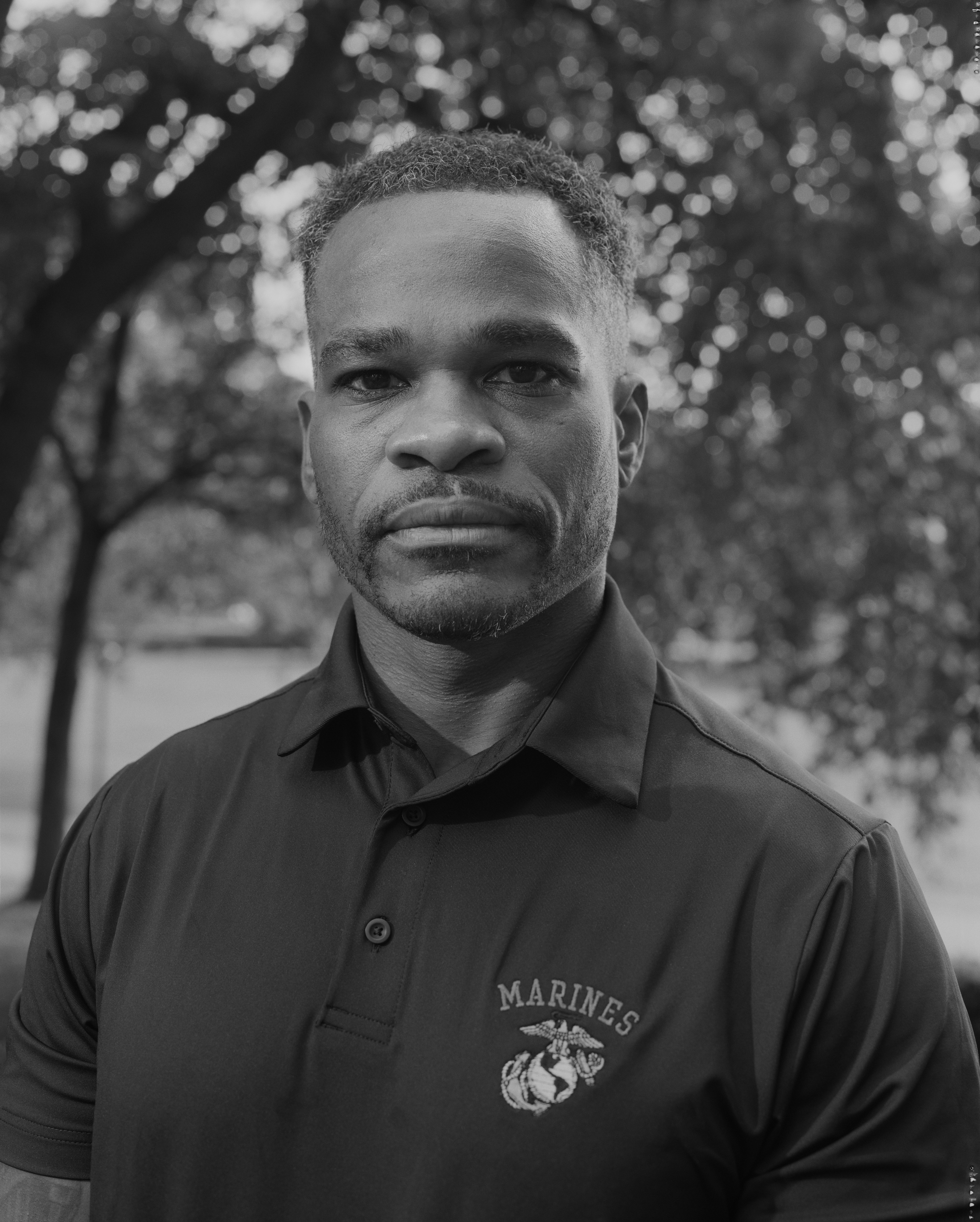

I prop my launcher on my thigh as my crew chief, Michael Briscoe, inserts a high-explosive rocket. Collectively, we dash to the center of the road. I prop the weapon on my shoulder and press my face towards the launch tube to look by way of the scope.

Bullets are hitting throughout us as Briscoe turns round to verify no Marines are standing behind us.

Dozens of them are. However there’s no time for protocol.

He slaps my shoulder and screams in my ear, “Backblast space all safe! Rocket!”

Ten kilos disappear from my shoulder immediately, and the second story of the home is destroyed.

The gunfire stops. For a second.

The enemy takes pot-shots over and round partitions as we transfer from one house to a different. We discover a community of blown-out partitions, permitting fighters to maneuver from home to deal with. Mattresses are boobytrapped with grenades and cutouts for individuals to cover inside. We discover tripwires and machine gun bunkers strengthened with sandbags.

Sgt. Leo usually takes level alongside Lance Cpl. Bradley Faircloth, clearing virtually each house we go into. He lobs grenade after grenade over compound partitions and has me blow open door after door with explosive expenses. Throughout the road, Gary Koehler will get shot in his leg, and Matthew “Doo Doo” Brown is shot within the buttocks like Forrest Gump. Then Brian Passolt takes a machine gun burst to the abdomen.

Again house, the three of them aren’t but sufficiently old to purchase a six-pack of beer.

They’re stacked into the again of a automobile like a twine of wooden and disappear into the gap.

By dusk, we’re nonetheless clearing our first avenue inside town and occupying a home for the night time. Some sleep in beds, others on pillows and piles of garments. I’m relegated to the rooftop with the boots and sleep beneath a blanket of stars between hour-long shifts of guard obligation.

The following morning, we get up earlier than dawn and proceed our weeks-long journey south.

Eat. Sleep. Shoot. Shit. Repeat.

For days, the firefights are fixed as we clear home after home. Machine gunners hearth from the hip as we rush down streets. I hearth dozens of rockets and we use so many grenades that we run out. I start to prime sticks of C4 for us to throw as an alternative. The blasts break prayer beads and tear Qurans.

Within the second, destroying heirlooms and wedding ceremony images throughout searches and defecating in bathtubs to keep away from being uncovered to enemy hearth outdoors really feel crucial. However they’re a few of the issues that hassle me most 20 years later.

At one level, an officer specializing in chemical weapons identification tells us that we’ve found drums of chemical weapons often called “blood brokers” and that we should always vacate the premises. We do as we’re instructed. We additionally uncover a torture chamber. A long time later, I nonetheless have nightmares the place I’m trapped in that small metallic cage.

One morning, our patrol stops on the fringe of an open discipline. We’re ordered to run throughout, and one after the other, we dash a whole lot of meters towards a cluster of three-story houses.

100 kilos of rockets and explosives press into my flak jacket as I rush throughout the uneven floor, dodging ankle rollers, barbed wire, and piles of filth.

Puffs of filth bounce from the bottom as bullets snap and whiz round us as our boots suck into the moist earth.

The charging deal with of my rocket launcher digs into my thigh with each step.

My gasps for air drown out the noises round me.

Someway, all of us make it.

We climb the steps of the constructing, and the squad man’s defensive positions on each flooring. The Marines on the roof take cowl behind a brief wall and start to return hearth as enemy fighters take pot-shots from close by home windows and scurry by way of alleyways.

Our lieutenant rapidly realizes we’re at a tactical drawback. We’ve been holding our place for too lengthy, and the enemy has surrounded us on three sides.

Shell casings pile up at our combating positions as enemy tracer rounds penetrate the wall and dance throughout the rooftop till they fizzle out. Speaking machine weapons play a sport of rebel whack-a-mole. I watch fixed-wing plane drop bombs within the distance.

Mike Ergo, a 21-year-old from Walnut Creek, California, who joined the Corps to play the saxophone, is on the roof smoking a cigarette and scanning for enemy fighters when he hears a whoosh as a volley of rockets slams into the entrance of our constructing. The blast briefly knocks him unconscious.

As Ergo pulls himself off the bottom, he sees the wall beside him is destroyed. He hears gunfire and tastes explosive residue.

“I’m hit,” Sgt. Leo screams from close by, because the wall explodes round him. He clutches his leg. A deep purple bruise rapidly spreads throughout his hip and thigh. Then Sgt. Nathan Fox, a 21-year-old from Berryville, Virginia, takes shrapnel within the shoulder. Ergo and one other Marine rush to tug them from the roof.

I watch as our wounded are carried downstairs. Leo objects all the time. He’ll stroll it off, he jokes. Our lieutenant worries Leo’s femur is damaged and forces him to depart, assuring him he’ll return quickly.

For the primary time, we see worry in Leo’s eyes.

Because the firefight continues, our wounded are pushed to the hospital. Morale crumbles. There’s an apparent void as we proceed to push by way of town.

Sgt. Leo was extra of a safety blanket than we’d realized.

We’re on an afternoon patrol once I see a Marine from one other battalion diddy bopping with a gnawed femur and pelvis resting over his shoulder as if he had been a fight bindle stiff.

“Have a look at how small his dick is,” he jokes as he tosses the stays on the bottom. I wind my disposable digicam and snap {a photograph} of him bent over, smiling beside the bloody genitals. Once I have a look at the picture now, the Marine stares again at me from beneath his kevlar helmet. His face is stuffed with pleasure. On the time, I used to be comfortable, too. Twenty years later, I really feel contempt towards our indignity.

We’ve been inside Fallujah for weeks and have embraced the kill-or-be-killed actuality surrounding us. After we see Marines from mortuary affairs start amassing enemy stays for intelligence gathering at The Potato Manufacturing facility—the part of the federal government heart the place enemy our bodies are being collected—I watch from a distance as limbs deglove and meat sloughs from bones. The aroma of bloated, rotting corpses and firefights has turn out to be our norm.

We’re absent of emotion and humanity. Numb.

However now Marines throughout Fallujah are ordered to go on patrol and kill the animals roaming the streets.

Canine are sick from consuming the decomposing our bodies, and we’re instructed the executions are to forestall the unfold of illness.

Killing animals is a line I received’t cross. Listening to their helpless yelps and screeches is insufferable. However watching them run towards us for assist as soon as they’re wounded is torturous.

A number of days later, we start taking hearth from a second-story constructing and rapidly encompass it.

The enemy is trapped inside.

A rocket is fired. Machine gunners sprinkle ammunition by way of home windows and doorways. Others hurl grenades. The jihadis on the opposite facet do the identical.

I scream degrading feedback about Islam, devoid of the disgrace that can metastasize.

Our interpreter—an Iraqi citizen from a village outdoors of Baghdad—yells for the fighters to place down their weapons and are available out with their palms up.

They refuse.

We attempt to persuade them with one other volley of grenades, gunfire, and slurs about Islam.

Then a Marine runs over to the driving force of a close-by D9—a 54-ton bulldozer—and asks them to demolish the home so we received’t must go inside.

The bottom shakes as the driving force positions the automobile a number of ft from the constructing.

Rocks crumble underneath the tracks because the blade lowers and the automobile inches ahead.

The partitions fold in, and the second story buckles as the driving force works his manner across the construction.

We watch as the house is slowly compressed right into a pile of twisted rebar, damaged cinder blocks, and tattered belongings.

We cheer.

I discover that our interpreter doesn’t.

The insurgents go silent.

However 20 years later, I nonetheless hear them scream.

We proceed our patrol again to base.

It’s time for chow.

Later that week, the streets are quiet. We transfer between homes and slender alleyways, anticipating to return underneath assault for hours. Nothing.

As we’re turning again to base, a shot rings out. Then one other. Sniper. I’m a number of doorways down and wish to hearth a rocket into the constructing, however Marines are ordered to storm the compound as an alternative.

Two Marines from our platoon, Bradley Faircloth and Michael Meadows, push by way of the gate and clear the courtyard. They discover the home windows are coated with blankets and that the entrance door is unlocked.

As they step into the lounge, there’s a stairway to their left and two rooms in entrance of them. One door is open. The opposite closed.

Faircloth leads Meadows down the hallway—he’ll go left. Meadows goes proper.

As they stroll towards the doorways, a machine gun erupts with a 20-round burst. Faircloth moans as he collapses to the ground.

Meadows sprints by way of the open door and requires reinforcements. Ryan Stulman and their squad chief, Evan Matthews, rush inside to clear the home, however the enemy fighters escape.

The three Marines seize Faircloth by his limbs and scream for a corpsman as they carry him outdoors.

Faircloth’s head bobs up and down with each step. His lips are blue. His eyes are open.

Corpsman up! Corpsman! CORPSMAN!

They set his physique down within the courtyard, and our corpsman Reinaldo “Doc” Aponte begins his evaluation. Airway. Respiration. Circulation.

Doc reaches to examine for a pulse, and his fingers slip inside a wound on Faircloth’s wrist.

No pulse.

He tears open Faircloth’s flak jacket and sees gunshot wounds to his flank.

There’s little or no blood.

No rise and fall of his chest.

Doc intertwines his fingers and facilities his palm on Faircloth’s sternum.

Ribs and cartilage break with every two-inch-deep chest compression.

However Faircloth’s accidents are too intensive.

There’s nothing Doc can do to avoid wasting his affected person.

Doc needs to be pulled off of Faircloth’s physique.

Tears stream down his face as he’s embraced by the Marines round him.

Doc is 21 years previous.

Our platoon is scattered, and many people don’t but know Faircloth is lifeless.

The firefight continues.

Sgt. Anthony Martinez is on a close-by rooftop and shoots two fighters scurrying to a close-by constructing. Lt. Bahrns does the identical. Robert Day pulls the set off of his machine gun and fires on the home.

Then I see two insurgents dash down an alleyway right into a compound.

Squirters.

I shoulder my rocket launcher and hearth of their route. Three partitions of the constructing collapse, and the home folds outward.

I run with three different Marines towards the collapsed construction and discover two our bodies mendacity outdoors, blown clear by the blast.

I stare on the figures. One is mangled and lacking each legs. Blood swimming pools beside his torso.

Then I hear somebody yell out {that a} Marine has been killed storming the compound.

My eyes sting from sweat and tears of frustration.

Weeks of heavy fight have put me on edge. Mates have died; others have been wounded, some a number of occasions.

Now the enemy fighters lay lifeless on the bottom in entrance of me.

I feel to myself that if I had fired my rocket into the constructing, a Marine would possibly nonetheless be alive.

We’re instructed it’s Lance Cpl. Bradley “The Barbarian” Faircloth, a 20-year-old from Cellular, Alabama. He’s a Sgt. Leo within the making and extensively considered the perfect boot within the platoon.

We watch from a distance because the physique bag is zipped closed and loaded into the again of a automobile.

Many people cry as we proceed our patrol again to base.

After we return, there’s silence as we eat our vacuum-sealed meals of preservatives and congealed fat. Meadows needs he’d thrown a grenade and killed the lads who shot Faircloth. Matthews wonders if his squad will ever belief him once more. Bahrns believes he let down Brad’s household again house.

Doc is inconsolable and believes he failed us by not saving Faircloth. That he’s misplaced our belief. And that by dropping Faircloth, he’s misplaced us all.

All of us know there will probably be a memorial service after we get house and are scared about what will probably be prefer to look Bradley’s mom in her eyes.

As the times go on, we reminisce about Faircloth and the Thanksgiving dinner we shared with him the day earlier than he was killed. Our lack of motivation is palpable. We wish to go house. However we nonetheless have two months left on our deployment.

Over the following few weeks, Leo nominates roughly half of our squad for valorous awards. The Corps’ paperwork mows most of them down.

The following month, our battalion commander Lt. Col. Gareth Brandl begins making his rounds to speak to Marines throughout the battlespace. We take out the trash and shave our faces. We shirt our boots and placed on our cleanest uniforms. It’s our flip for the canine and pony present.

When he arrives, we stand neatly in a formation as he speaks for what looks like an hour—tales of our bravery and sacrifice and the way we upheld the Corps’ legacy.

Yut. Err. Kill.

One sentence lingers in our minds. Put together to your subsequent mission.

Widows and different Gold Star relations sit within the entrance rows of a silent theater.

It’s the spring of 2005, and we’ve been house for a number of weeks. Our whole battalion is crammed into the bottom discipline home at Camp Lejeune. Dozens of portraits are displayed on the ground, every paired with a rifle, canine tags, and boots.

I stare on the pictures. They stare again.

They’re all lifeless.

For months, we’ve struggled with our battle, however we’ve remained remoted from the households who obtained the dreaded knock on the door to mark the beginning of their vacation season. We weren’t there for his or her three-volley-gun salute, or once they had been handed a folded flag “on behalf of a grateful nation.”

Now, seated within the bleachers, we’re too far-off to consolation them.

Doc can’t bear to look at Kathleen Faircloth stroll throughout the ground. He sneaks outdoors and cries within the cab of his truck.

I sit quietly and recall my occasions on the Faculty of Infantry with Demarkus Brown, who liked to inform tales about his mom.

I feel again to my conversations with Lt. Malcom about his sister.

I keep in mind my late-night conversations with Travis Desiato about being proud Massholes.

I take into consideration how a lot I wish to apologize to Kathleen Faircloth, however I can’t face her.

One after the other, the households are ushered throughout the ground, and one after the other, they stand by the pictures of their family members. Some pray. Others hug. Most of them cry.

Youngsters with no fathers. Mother and father who misplaced sons. Households destroyed. Mates we’ll by no means see once more. All torn aside by fight 1000’s of miles away throughout a conflict that America ignored.

As every household walks again to their seats, the regular rhythm of their footsteps is a reminder of how we didn’t deliver their family members house.

The sound of faucets fills the constructing.

I stare straight ahead and take a look at to not let anybody see me crying. It’s a sense I’ll get used to.

Twenty years in the past, I assumed the Corps gave me precisely what I requested for, and I’m nonetheless struggling to grasp the that means of all of it.

Once I enlisted in 2003, I used to be a rebellious teenager who lacked self-discipline and a way of objective. Regardless of my mom’s objections, I needed to be a Marine infantryman. Once I acquired to recruit coaching at Parris Island, the Corps handed me my first rifle and taught me that blood makes the grass develop. In Fallujah, we destroyed our enemy by way of hearth and maneuver—precisely what we had been educated to do.

The foundations of engagement justified the loss of life and destruction. However as we speak, I now not can.

After we got here house, we settled into the monotony of grocery buying, altering diapers, and paying utility payments, all whereas we confronted a rampant stigma disincentivizing psychological well being care. Dozens of Marines throughout our battalion self-medicated with medicine and alcohol. Those that had been caught had been publicly shamed and booted from the Corps.

I finally tried to kill myself.

The fog of conflict might have been in Fallujah, nevertheless it nonetheless drifts out and in of our lives, usually on the most inopportune, sudden occasions.

Just like the time my daughter and I had been taking part in with dolls on the ground and their chilly, lifeless eyes jogged my memory of a lifeless physique.

Or when the scent of jet gas on the airport made me think about operating alongside a tank, smiling with my associates.

Or when AC/DC’s “Hells Bells” came to visit the audio system as my spouse and I waited in line to trip a curler coaster. My thoughts drifted to crossing Route Fran, and reminiscences of Malcom and Faircloth.

I stared straight ahead and tried to not let anybody see me crying. The sensation I’m now used to.

And now, after twenty years spent making an attempt to overlook what we noticed and did in Fallujah, I made a decision it was time to confront it. I reached out to Marines I hadn’t spoken to for the reason that battle, and with them by my facet—identical to they had been 20 years in the past—I wrote this story.

In August, I organized a five-day reunion in DC that introduced our squad again collectively. We cried. We laughed. And we remembered. However probably the most therapeutic a part of our time collectively was that Faircloth’s mom, Kathleen, traveled from Alabama to hitch us and lead us into the brand new Fallujah exhibit on the Nationwide Museum of the Marine Corps.

Collectively, we listened to her learn the final letter Bradley wrote house.

And never solely had been we in a position to look Kathleen within the eye however she instructed us one thing that can by no means depart me.

We’re all her sons.

Like tens of millions of Individuals, I volunteered to serve throughout a time of conflict and knew I would expertise fight. We trusted the Pentagon officers main us and the promise that we’d be cared for as soon as we returned house. We believed the worldwide conflict on terror was justified and that by combating it, our youngsters wouldn’t face the identical enemy. We believed Individuals cared concerning the conflict we fought on their behalf.

We must always have recognized higher.

After 20 years, what haunts me most about Fallujah isn’t simply the killing or how we did it, whether or not it was a bullet, a blast, or a bulldozer.

It’s figuring out that a few of the hope we destroyed in Fallujah was our personal.

The hope that point will make the reminiscences fade away.

The hope that I’ll forgive myself.

And the hope that it was all price it in the long run.

When you or somebody you care about could also be vulnerable to suicide, contact the 988 Suicide and Disaster Lifeline by calling or texting 988, or go to 988lifeline.org.

The Folks Who Made This Venture Attainable

AuthorThomas J. Brennan

PhotographyMatt EichJustin GellersonCpl. Trevor GiftMadison Brennan

VideoTJ CooneySunjae SmithShane YeagerClaude RobinsonJohn NapolitanoGreg Corombos (AVC)Dan Taksas (AVC)Peter Trahan (AVC)Vallen King (AVC)Wealthy McFadden (AVC)Nick Schifrin (PBS Newshour)Paul Wooden (BBC Embedded Footage)Robbie Wright (BBC Embedded Footage)

AudioElena BoffettaJim O’Grady (Reveal from the Heart for Investigative Reporting)

EngagementLydia Williams Keller (Soundview Inventive)Hrisanthi Kroi Pickett

Reality-CheckJess Rohan

Copy EditsMitchell Hansen-Dewar

EditorsMike FrankelDan Schulman (Mom Jones)

Music LicensingJonathan Leahy, Aperature Music (In-Sort Advisory Assist)Phil Collins through Harmony Publishing and Warner Music Group (Free of charge)Lynyrd Skynyrd through UME and UMPG (Free of charge)AC/DC through Sony and Sony Music Publishing (Free of charge)

PartnersMother JonesPBS NewsHourThe Heart for Investigative ReportingThe American Veterans Heart

Location SupportLt. Col. Matthew Hilton, USMC Communications Directorate, New YorkCol. John Caldwell, Communications Directorate, Headquarters USMCThe Nationwide Museum of the Marine CorpsOffice of the Secretary of DefenseThe United States Marine Corps

Psychological Well being Dr. Pamela WallJodi Salamino

Authorized ReviewBakerHostetlerJames Chadwick (Mom Jones)4 Retired Marine Choose Advocates